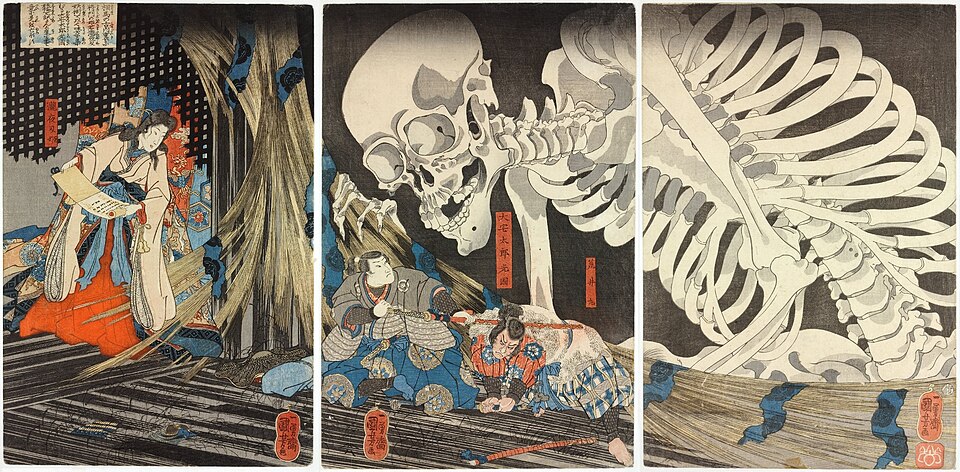

Few images in global art history have achieved the mythic resonance of Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Even people who have never heard of ukiyo‑e, Japanese woodblock printing, or Hokusai himself can instantly recognize that towering blue crest, frozen at the moment before it crashes down on the fragile boats below. The work has become a visual shorthand for nature’s power, artistic elegance, and the cultural imagination of Japan.

Hokusai created The Great Wave around 1831, when he was in his seventies—an age when most artists would have long settled into their style. Instead, Hokusai was in the midst of a creative rebirth. The print is part of his celebrated series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,” a collection that explores Japan’s sacred mountain from multiple angles, moods, and distances.

What makes this particular print extraordinary is how it blends tradition with innovation. Hokusai uses the established ukiyo‑e technique, yet he pushes it into new emotional and visual territory.

The wave itself is the star of the composition. Its curling crest resembles claws or teeth, giving it an almost animate presence. The foam breaks into delicate tendrils, each one carved with astonishing precision. The wave is not merely water—it is a force of nature, a character with its own will.

Below it, three long, narrow fishing boats—oshiokuri-bune—race across the turbulent sea. The rowers lean forward in unison, their bodies taut with effort. They are dwarfed by the wave, yet they do not panic. This tension between human resilience and natural power is one of the print’s most compelling themes.

In the background, almost easy to miss at first glance, sits Mount Fuji. Calm. Unmoving. Eternal.

Hokusai contrasts the mountain’s stability with the wave’s explosive motion. This juxtaposition creates a philosophical undercurrent: the fleeting versus the eternal, the violent versus the serene, the human moment versus the timeless landscape.

Hokusai’s use of Prussian blue, a relatively new pigment in Japan at the time, gives the print its distinctive depth and vibrancy. The color was expensive and exotic, and its adoption shows Hokusai’s willingness to experiment.

The composition is equally daring. Instead of centering Mount Fuji, he places it off to the side, letting the wave dominate the frame. The diagonal sweep of the boats and the circular arc of the wave create a dynamic tension that feels almost cinematic.

When Japan opened to international trade in the mid‑19th century, prints like The Great Wave flooded into Europe. They captivated artists such as Van Gogh, Monet, and Whistler, helping spark the movement known as Japonisme. The print’s influence can be traced through Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and even modern graphic design.

Today, The Great Wave appears everywhere—from museum walls to tattoos, from fashion to emojis. Yet despite its ubiquity, the original retains a quiet, enduring power.

The Great Wave endures because it captures something universal:

the awe we feel before nature

the fragility of human life

the beauty found in moments of tension

the harmony between chaos and calm

It is a reminder that art can be both simple and profound, both local and universal. Hokusai distilled an entire worldview into a single moment of suspended motion.