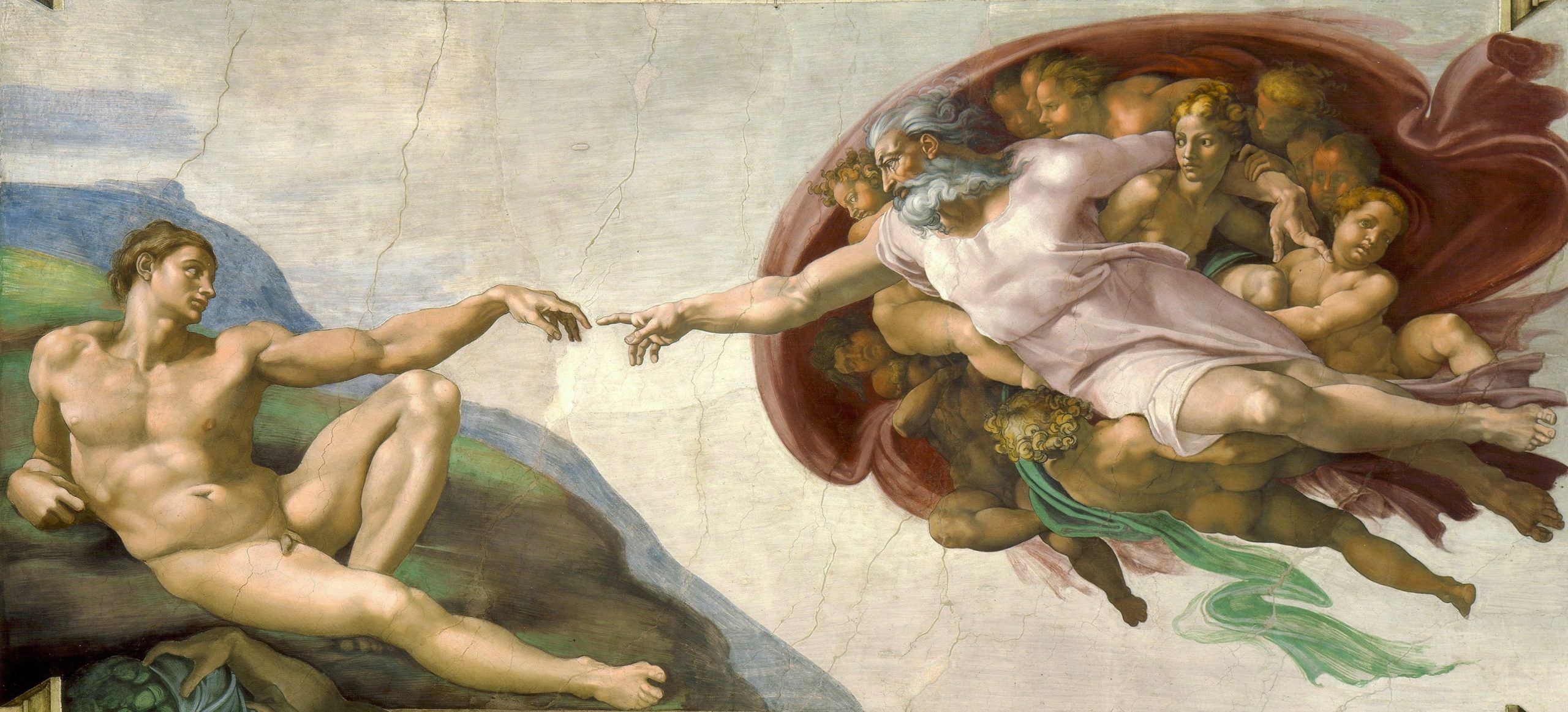

Few images in Western art have achieved the cultural resonance of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam. Painted around 1511 on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, this fresco has become a universal symbol of human potential, divine inspiration, and the mysterious spark that connects the mortal to the eternal. More than a religious illustration, it is a philosophical statement rendered in color and anatomy.

1. Historical Context: A Monumental Commission

When Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the artist was already renowned as a sculptor, not a painter. Yet Michelangelo approached the project with the same sculptural sensibility that shaped his David and Pietà. The ceiling’s vast program—over 300 figures—depicts the drama of Genesis, but The Creation of Adam stands at its emotional center.

Painted during the High Renaissance, the fresco reflects the era’s confidence in human dignity, intellectual curiosity, and the rediscovery of classical ideals. Michelangelo fused these humanist values with Christian theology, creating an image that transcends its biblical source.

2. Composition: A Moment Suspended in Time

At first glance, the fresco captures a simple gesture: the nearly touching hands of God and Adam. But Michelangelo’s composition is a masterclass in visual storytelling.

Key elements of the composition

- Adam, reclining on the barren earth, is depicted with the idealized beauty of classical sculpture. His body is relaxed, almost passive, as if awaiting the vital spark.

- God, dynamic and muscular, rushes forward enveloped in a swirling mantle of angels. His movement contrasts sharply with Adam’s stillness.

- The Hands, placed at the center of the fresco, form the emotional and symbolic climax. The tiny gap between the fingers is charged with tension—the instant before life is bestowed.

This moment is not the act of creation itself, but the anticipation of it. Michelangelo captures the threshold between non-being and being, between potential and realization.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

The Divine Spark

The almost-touching hands have become a metaphor for inspiration, creativity, and the human longing for transcendence. The space between them is often interpreted as the fragile boundary between humanity and divinity.

Human Dignity

Adam’s pose mirrors God’s, suggesting that humanity is created imago Dei—in the image of God. This visual parallel reinforces Renaissance humanism’s belief in the nobility and potential of the human being.

The Mysterious Mantle

One of the most debated elements is the shape of the mantle surrounding God. Some scholars argue that it resembles:

- a human brain, symbolizing divine intellect, or

- a uterus, symbolizing birth and creation.

Whether intentional or not, these interpretations highlight the fresco’s layered complexity.

4. Michelangelo’s Mastery of Anatomy and Emotion

Michelangelo’s deep knowledge of the human body—gained through years of studying classical sculpture and dissecting cadavers—infuses the fresco with a sculptural realism. Muscles, torsos, and limbs are rendered with precision, yet they never feel static. Instead, the figures pulse with life and psychological depth.

God’s intense gaze, Adam’s serene acceptance, and the swirling energy of the angels create a narrative that is both intimate and cosmic.

5. Legacy and Cultural Impact

The Creation of Adam has become one of the most reproduced and referenced images in art history. Its influence extends far beyond religious contexts:

- It appears in films, advertisements, and literature.

- It has inspired countless reinterpretations, parodies, and homages.

- The image of the two hands has become a universal symbol of connection, creativity, and aspiration.

Despite its ubiquity, the fresco retains its power. Standing beneath the Sistine Chapel ceiling, viewers still feel the awe Michelangelo intended—a sense of witnessing the birth of humanity.

Conclusion: A Timeless Dialogue Between Earth and Heaven

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam is more than a masterpiece of Renaissance art; it is a meditation on existence itself. Through a single gesture, Michelangelo expresses the profound relationship between the human and the divine, the physical and the spiritual, the finite and the infinite.

It remains a testament to the enduring capacity of art to capture the deepest questions of the human condition.