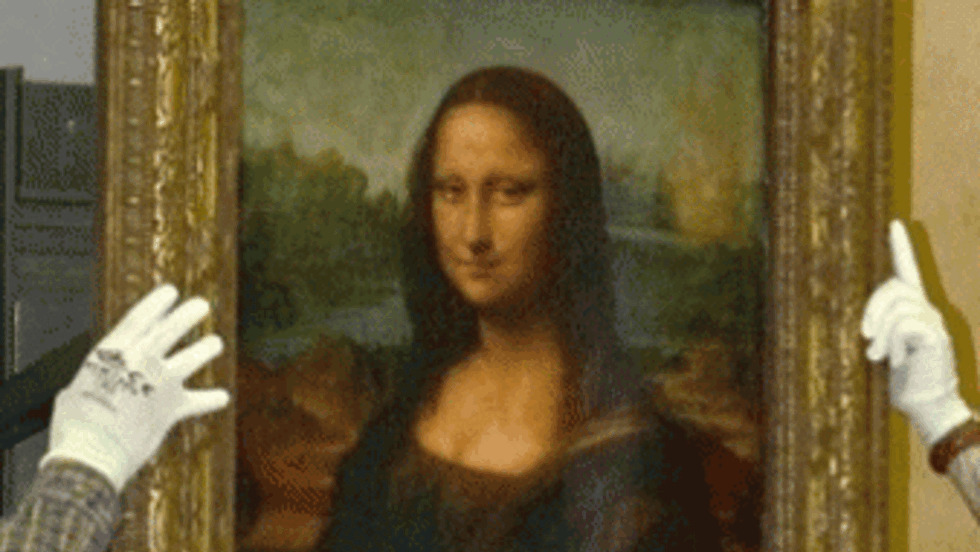

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne is an unfinished oil painting by Leonardo da Vinci, created between around 1501 and 1519. It portrays Saint Anne, her daughter the Virgin Mary, and the infant Jesus forming a harmonious triangular composition that exemplifies High Renaissance ideals.

During the early 1500s, Leonardo’s career spanned courtly patronage and scientific exploration. Scholars believe the work was commissioned by King Louis XII of France shortly after the birth of his daughter in 1499, though the painting never reached him. It was intended as the high altarpiece for the Church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence, reflecting Leonardo’s longstanding fascination with this familial subject.

Composition and Iconography

Leonardo arranges the figures in a gently pyramidal structure, with Mary seated on Saint Anne’s lap and Jesus engaging with a sacrificial lamb. This lamb symbolizes Christ’s future Passion, while the tender interactions among the three females underscore themes of maternal lineage and divine grace. Leonardo subtly enlarges Saint Anne relative to Mary, emphasizing the generational bond without relying on explicit age markers. Leonardo’s use of sfumato softens the contours between figures and background, creating depth and a sense of atmospheric unity. Infrared reflectography has revealed faint sketches on the reverse of the panel—a horse’s head, half a skull, and an infant Jesus with a lamb—demonstrating his habit of reusing support surfaces for anatomical and compositional studies.

After Leonardo’s death, the painting remained in Italy until King Francis I of France acquired it. Today, it resides in the Louvre Museum. Ongoing research by Louvre conservators continues to uncover Leonardo’s underdrawings and pigment choices, offering fresh insights into his working methods and unfinished intentions. Leonardo’s portrayal of intergenerational intimacy inspired later artists far beyond his era. For instance, Max Ernst’s 1927 painting The Kiss pays homage to Leonardo’s triangular grouping and affectionate gestures. Leonardo’s Burlington House Cartoon, created in 1498, further explores similar figure relationships and served as a crucial preparatory work for this altarpiece.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne stands as a testament to Leonardo da Vinci’s genius in uniting complex iconography, pioneering techniques, and emotional depth. Even unfinished, it invites viewers into an intimate meditation on family, faith, and the mysteries that captivated the artist throughout his life.